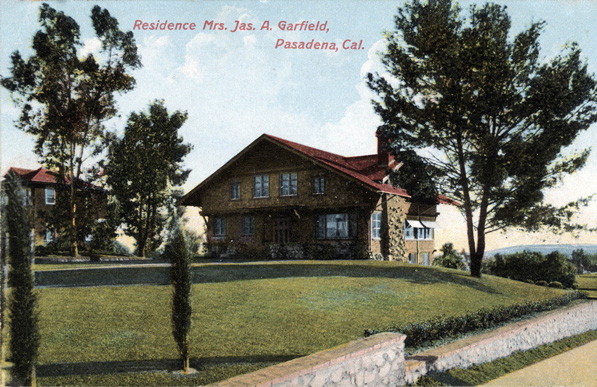

Lucretia Garfield’s correspondence with Charles Greene begins in May 1903, after she had spent some months in Pasadena. At the time, the Greenes had just completed plans for the Darling house in Claremont, and had several projects underway, including houses for Arturo Bandini, Josephine Van Rossem, Edith Claypole, and Jennie Reeve in Long Beach. How Mrs. Garfield learned about the Greenes is not clear, but it may have been through her family connection to the New England Greenes, also relatives of Charles and Henry. In one of her letters, she recommended a book on the Greenes of Rhode Island, the branch of the family from which Charles and Henry were descended.

Greene & Greene drew up plans for her lot on Buena Vista Street in South Pasadena, but Mrs. Garfield, citing her architect son as her adviser, had many changes to make, and was most concerned about the cost. Charles responded to her suggestions with the news that “this will cause some delay and expense. . . in fact, we shall have to begin over again. . . and the extra cost of plumbing may make the house a little more expensive.” He added: “The reason why the beams project from the gables is because they cast such beautiful shadows in this bright atmosphere.”

After more exchanges, Mrs. Garfield decided to postpone the project, although she found the whole plan and specifications so satisfactory that she wanted “to keep it just as it is.” Clearly the cost estimate of nearly $11,000 had given her pause, and she expressed the hope that “a little delay may bring a lower bid.”

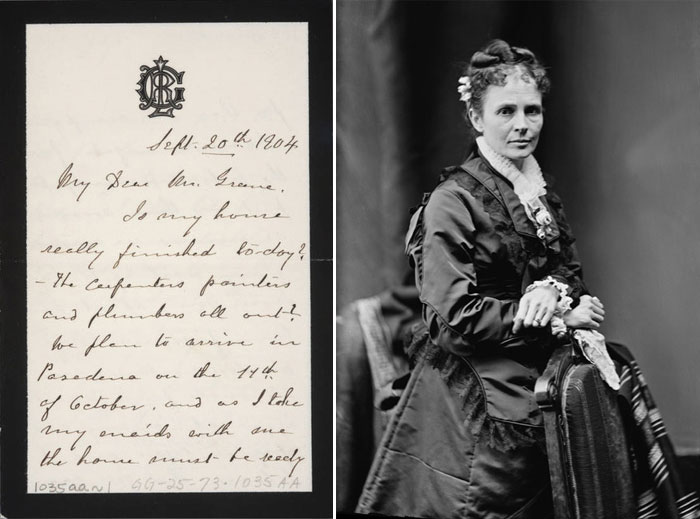

Running through all of her letters is her concern about cost. Lucretia Garfield was a well-off woman for the time, with a $5,000 annual government pension ($145,000 today), and a trust fund of $350,000 (now over $10 million) for herself and her children. She also was not alone among the Greenes’ clients who expressed concern about when her house would be finished. Writing on black-bordered stationery, the widow of the assassinated President Garfield reminded all her correspondents of her personal tragedy, even 20 years later.

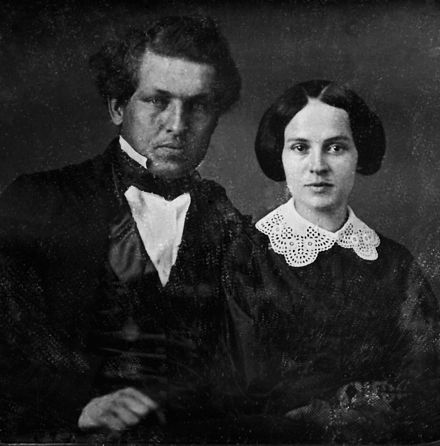

Lucretia Rudolph and James Garfield had attended grammar school and college together, and although he was only a few months older, he was her Greek professor at the Eclectic Institute, the small college she attended in Hiram, Ohio. Lucretia was unusual for her time, a young woman pursuing a college education. She specialized in the Classics, studying Latin and Greek, as well as French and mathematics. James came from a broken home, and worked driving mule teams that pulled river barges in Ohio. Felled by an illness when he was 17, he began to study, found he was good at it, and progressed quickly, entering the college where he was also hired to teach Greek. Lucretia was his star student and caught his attention. Garfield, also an outstanding student, pursued more education, leaving Ohio to attend Williams College in Massachusetts, where he initiated a correspondence with “Crete,” who had graduated and was following the female profession of teaching, and living on her own. Although the mutual attraction was founded on intellectual interests, both hesitated to commit to the relationship, because she did not display outright emotion or physical affection for him. Despite this, they married in 1858.

Garfield pursued a career in law, and his oratorical gifts led him into politics, first in the Ohio State Senate, then following service in the Civil War, in Congress, the US Senate, and finally the Presidency in 1881.

In the course of their marriage, Crete bore seven children, five of whom survived to adulthood. She also supervised the building of their home in Washington, where she had a room to herself, to read, paint, and write.

Educated and independent, she was one of the first presidential candidate’s wives to appear on a campaign poster. She played a public role in Garfield’s innovative “front porch” campaign, conducted from “Lawnfield,” their home in Mentor, Ohio, where the candidate met the public. James took her advice on political questions during the campaign, the transition, and later once he was president. As First Lady, Lucretia made plans to invite cultural leaders to the White House, and to restore some of the rooms to their original appearance. Following Garfield’s assassination only a few months into his presidency, she withdrew from public life, focusing on preserving her husband’s legacy. She actively participated in the design of the Garfield Monument in Cleveland, and she established the first presidential library at “Lawnfield,” preserving her husband’s letters for future research and publication.

Like many Midwesterners, she eventually sought out the mild climate of Pasadena to spend the winters. Besides her experience building the Washington house, she had also supervised many additions to “Lawnfield,” which grew from a farmhouse into a Victorian mansion.

In his letter to Mrs. Garfield following her decision to postpone her project in South Pasadena, Charles promised to work further on the plans. In her next letter the following March she suggests additional alterations, adding “Bring the contractor’s bid down to $6,000, if possible,” quite a change from the $11,000 of the previous year. By May the house was underway, and Lucretia was already sending checks to the contractor, August Brandt. Building was proceeding quickly in the summer of 1904. In June she inquired about planting the grounds, adding brick walks and a trellis for the clothes yard.

On September 20, 1904, she writes:

“My dear Mr. Greene,”

Is my house really finished today? The carpenters, painters, and plumbers all out? We plan to arrive in Pasadena on the 14th of October, and as I take my maids with me the house must be ready for them to occupy it. I have arranged for the beds to be ready to put in their rooms as soon as we arrive. I am waiting to hear from you about curtain fixtures. My window curtains are all made for a small brass rod or any rod of equal size, and if I learn that you can design and put them up for less than the price quoted in my letter, I will let you know immediately so that you may have them ready by the time we arrive.”

“I beg your pardon for having mislaid the table of regulations regarding architect’s fees and for not having remembered what they are.”

Yours sincerely,

Lucretia R. Garfield”

Perhaps at this early stage of his career, Charles might have taken the trouble to design curtain rods “for less than the price quoted,” and had them put up for his famous client, but having to remind the client about the architects’ fees that were due and responding to questions about whether the work would be finished on time would become a recurring theme in the Greenes’ architectural practice. Still, the strength of the relationship would be demonstrated when the English Arts and Crafts luminary Charles Ashbee visited Pasadena in 1909. Charles Greene arranged for his famous guest to meet Mrs. Garfield, who invited them to take tea with her in her home by Greene & Greene.

Leave a Reply