Arts & Crafts in Pennsylvania [Part two]

by Anne Mallek

My first exposure to the work of Frank Lloyd Wright was as a naïve 12 year old on vacation with my family for two weeks in the seaside town of Carmel-by-the-Sea, the former bohemian artists’ community and home to writers like George Sterling and Robinson Jeffers, and architects such as Charles Greene. The house we rented belonged to friends of my grandparents, whose family had built their redwood and stone house on Scenic Drive sometime in the 1930s. It happened to be across from Wright’s 1948 house for Clinton and Della Walker (Clinton was the brother of Willis Walker, for whose wife Charles Greene had designed a stable in Pebble Beach in 1926). The Walkers’ house was to be a “Cabin on the Rocks,” situated—much as Greene’s D.L. James house—on a rocky promontory, with its broad, projecting copper roof and panoramic band of windows facing the sea. To the child that I was, its stubborn-faced gate that never appeared to open made it nearly anonymous, as the gate and roof were all one could see from the street. I could catch glimpses of the house from the beach or further down the road, but it remained aloof and a mystery as if designed to capture one’s curiosity about how the interiors of such a house must look, or who might have attempted such a feat in the first place. I don’t believe anyone ever told me that the house was by Wright – it was left for me to discover later for myself, at about the same time that I was cataloguing the William Morris collection at The Huntington and learned that it had been acquired from a couple on Scenic Drive, just up the road from where our family had stayed. Their Morris & Company stained glass had hung across their front windows that faced the sea. Life is, happily, full of such coincidences and crossings.

Its conception came about in the space of a morning…Wright created the first plans and elevations in the time that it took Edgar Kaufmann to drive to Taliesin from Milwaukee

In the last newsletter I shared with you a few Arts and Crafts sites in and around Philadelphia, discovered during the course of a conference in September. I also visited Pittsburgh, and to finally make the pilgrimage to Wright’s famed Fallingwater. The long drive to Mill Run eliminated all trace of the city, just as it might have done for the Kaufmanns in the 1930s, when they fled business and bustle for the calm of nature at their summer camp along the stream known as Bear Run. It was a rainy day when we visited (with my boyfriend and his family, all natives of Pittsburgh), and the joke of “falling water at Fallingwater” was repeated ad nauseam throughout the afternoon. I first took the standard docent-led tour, but had also booked the In-Depth tour, which allowed the visitor more time within and about the house, as well as the freedom to photograph at will, interiors and exteriors alike.

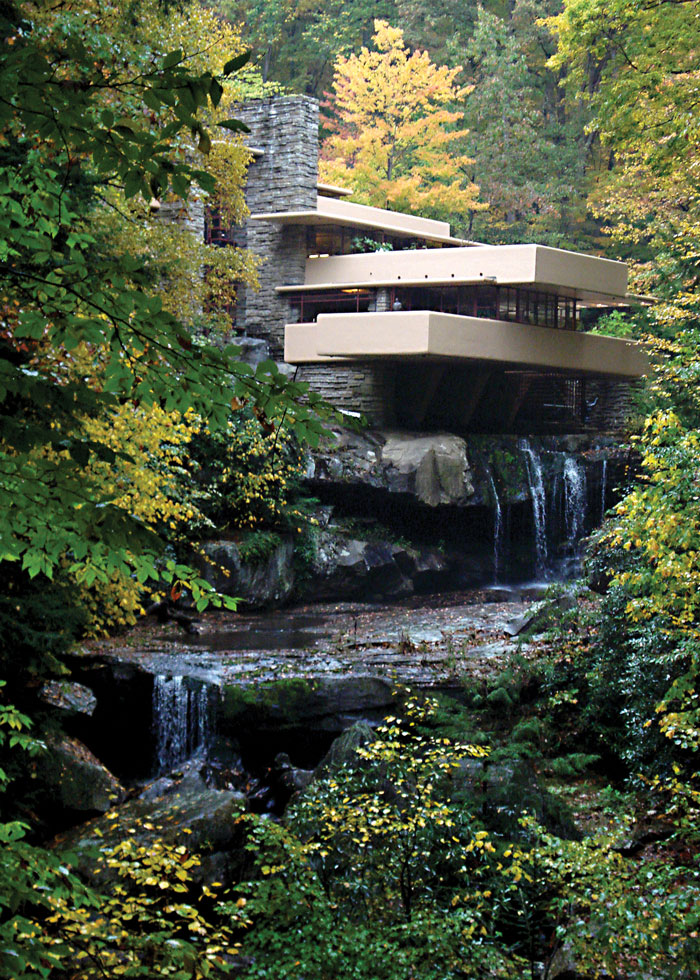

Both tours began with a long, winding walk from the visitors’ center, a pavilion marooned amongst the dripping woods. It was not unlike approaching one of the 18th-century English country houses for which Lancelot “Capability” Brown designed the landscape – taking one by a circuitous route in order to surprise the visitor who at last achieves a view of the entire house. Fallingwater is indeed a surprise – described by Wright biographer Brendan Gill as having the effect of “an exceptional feat of magic onstage,” inspiring almost spontaneous applause. To me perhaps the most surprising discovery was that its conception came about in the space of a morning – that is, Wright created the first plans and elevations in the time that it took Edgar Kaufmann to drive to Taliesin from Milwaukee (just over two hours). One of Wright’s apprentices, Edgar Tafel, recounted that “The design just poured out of him…Poetry in form, line, color, textures, and materials, all for a greater glory: a reality to live in!” Cantilevered over Bear Run by nearly invisible concrete supports or “bolsters,” Wright convinced the protesting Kaufmann that to hover above the waterfall rather than possess a commanding view of it was far more desirable, for it was “to live with the waterfall.” Despite protests of an independent firm of Pittsburgh engineers, with whom Kaufmann consulted in his unease about the potential instability of this house of concrete trays, stone, and glass hovering precariously over the water, Wright won out on this point (even as he admitted defeat over his proposal to cover the concrete parapets in gold leaf). Interior spaces vary from the ingenious accommodation of an open casement window by a perfectly carved opening in a desktop, to the two adjoining corner windows that when opened eliminate the corner altogether. There is the cramped entry hall rising to the light and open living room/dining room, with its stairs down to the stream below. Wright’s ability to incorporate his domestic designs into their environment has been much celebrated, and Fallingwater is certainly built on, against, and partly of local materials – yet its appearance is almost otherworldly, like some extravagantly beautiful mushroom.

As striking as Fallingwater is within its surroundings, its near neighbor, Kentuck Knob, commissioned by Isaac Newton (“I. N.”) and Bernardine Hagan in 1954, is not as declarative, but embedded in the side of the knob, hardly raising a profile. This may also be because it is an example (if a rather high-end version) of Wright’s Usonian house designs. With their compact but open floor plans, carports in lieu of garages, and absence of any service quarters, they were intended to be a solution for low-cost single-family housing. Though kitchens can often be small and corridors somewhat cramped, these are eminently comfortable, homey dwellings – a visit to the Weltzheimer/Johnson house in Oberlin, Ohio (1947-49) revealed the same built-in furniture, clerestory windows with their whimsically punctuated wooden screens, gridded concrete floors, board and batten paneling and glass walls, all combine to convey a sense of warmth, light, and ease of living.

Returning to the idea of crossings and coincidences, these were most certainly an architect’s bread and butter, and were the foundation and sustaining source for Wright’s clientele. The Kaufmanns’ son, Edgar Jr., was an apprentice at Taliesin for a short time when his parents came to visit and first encountered Wright. Within months of the meeting Kaufmann Sr. commissioned several new projects from Wright, including a planetarium and a new office for him in his department store. The office interior is owned by the Victoria & Albert Museum in London (given by Edgar Jr. in 1974), and currently being displayed in an exhibit at the Tate Britain on Modernist artist Kurt Schwitters. Schwitters is credited with developing the concept of “Merz” or “the combination, for artistic purposes, of all conceivable materials” – perhaps an extension of the idea of the “Gesamtkunstwerk,” or “total work of art” that inspired the Greenes as well as Wright? The Hagans’ son was studying architecture at Princeton at the time they decided to commission Wright to build their house, which in turn had been inspired by a visit to business colleague and friend Edgar Kaufmann at Fallingwater.

My own crossings reveal further hints of Wright in my childhood that would certainly have been referencing his Usonian designs. My grandparents, a California physician and his wife, designed their Modesto home in collaboration with a local architect in 1957. My mother recalls that my grandmother had collected clippings from a variety of magazines of the time to give her ideas for their new home and its seven occupants (undoubtedly these included Sunset and House Beautiful among others, who were publishing the work of architects like Wright and Cliff May). These ultimately included clerestory windows, mahogany paneling, built-in benches, tables, and desks (the desktops in the girls’ bedrooms lifted to reveal a mirror), floors with radiant heating, glass walls along two sides of the living room, etc. It was all about a more thoughtful and aesthetic way of life, one that integrated the interior with the out-of-doors. These were principles that guided Wright and indeed the Greenes, which only serves to draw Mill Run and Pasadena that little bit closer together.

Leave a Reply