GREENE & GREENE FURNITURE

More labor? It barely registered in the exquisite examples from these brothers. What really mattered: Integrity, Beauty, and Utility

by Darrell Peart & Ted Bosley for American Period Furniture Magazine

Reprinted with permission Society of American Period Furniture Makers

Greene & Greene furniture holds a unique place in the history of American woodworking. It marked a high point in the American Arts and Crafts Movement, uniting superb craftsmanship with some of the most thoughtful and sensitive designs ever produced.

The Greenes’ architectural and furniture design peaked during the years of 1902–1910. The Industrial Revolution had taken firm hold in America beginning in the mid-19th century, and hand skills had rapidly lost ground to the machine. In a few short years, Henry Ford would take mechanization to an entirely new level. The momentum was clearly behind mass production, and quality often took a back seat.

The Arts and Crafts Movement was a reaction to this world of dehumanizing machines. It was admittedly a romantic backward glance to pre-industrial times and what was perceived to be a simpler life. The movement’s proponents labored to inspire renewed reverence for useful objects made by hand, with pride.

In England, the movement took a mostly purist form. Hand skills were honored above all, and pride in work returned. Furniture makers, such as Ernest and Sidney Barnsley, made a living without the use of machines, in small shops, laboring over one piece at a time.

In America, the movement took a somewhat different direction. Gustav Stickley, a leading voice of the movement, designed straightforward furniture that even those with limited hand skills could participate. Craft was honored, but excellence was often sacrificed at the expense of mass participation and production. Stickley embraced machines to eliminate drudgery, and also to make possible enough production to meet the demand he was enthusiastically creating—primarily through his popular magazine, The Craftsman.

GREENE & GREENE APPROACH

Charles (1868–1957) and Henry (1870–1954) Greene took yet a third approach. The use or avoidance of machinery was less the issue than taking a nocompromise approach to design. Whatever the design required was built, machine or no machine. The integrity, beauty, and utility of the finished piece of furniture were what mattered.

Unlike Stickley, the Greenes’ furniture was not simplified. Nor was it accessible to everyone. It was, in fact, exclusive in all regards. Only the wealthiest of clients could afford the Greene-designed houses and furniture, and only the most accomplished woodworkers could build to their specifications.

As a young man, Charles Greene dreamed of being an artist. As an architect, he devoted his creative energy almost exclusively to the designs of houses and furniture. Beauty and usefulness were of supreme importance. Charles Greene called it “architecture as a fine art.”1

His younger brother, Henry, expressed it equally well: “The whole construction was carefully thought out; there was a reason for every detail. The idea was to eliminate everything unnecessary, to make the whole as direct and efficient as possible, but always with the beautiful in mind as the final goal.”2

The Greenes’ approach did not go unnoticed. On a visit to America in 1909, Charles Robert Ashbee, a leading voice of the English Arts and Crafts Movement, singled out the Greenes’ work as equal to the finest English craftsmanship:“…[B]eautiful cabinets and chairs of walnut and lignumvitae, exquisite dowelling and pegging, and in all a supreme feeling for the material, quite up to the best of our English craftsmanship.”3

VITAL COLLABORATION WITH THE HALL BROTHERS

In their early years as a firm, the Greenes were unable to secure reliable and skilled craftsmen to execute their complex architectural and furniture construction. In 1904, the Greenes began collaborating with master builders Peter (1867–1939) and John Hall (1864–1940), whose interest in structural integrity held equal status with beauty. The Hall brothers formed a vital part of the Greene & Greene firm in Pasadena, California. The quality of work produced required much more than the usual designer/builder relationship. Their deep understanding of each other was absolutely essential.

The Greenes were lifelong woodworkers. As teenagers, they attended Calvin Woodward’s Manual Training School in St. Louis, where their day was divided evenly between intellectual subjects and drafting or crafts, such as machine-toolmaking and woodworking.

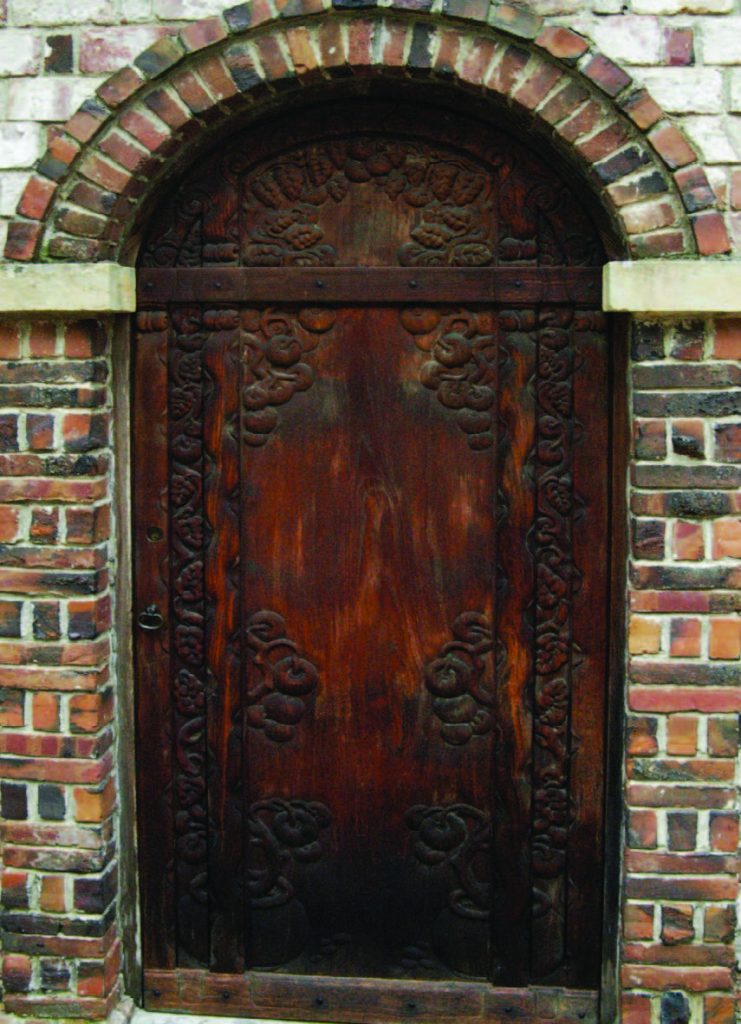

Charles Greene did not shy away wielding tools, and in later years practiced his carving skills professionally, as shown at left. Henry also was known to take on woodworking projects. Indeed, it is important to note that the Greenes had a good working knowledge of manual skills before they trained in architecture.

The Halls, more than most makers, learned the finer points of design at an early age. Their father most likely trained them at home in the Sloyd method, which placed a high value on teaching design and handcrafts as part of a child’s education.

Both the Hall brothers designed and built personal projects, but John especially had a solid design sense. Of his surviving projects, a mirror frame above illustrates his profound understanding of design, as well as his ability to assimilate the Greene & Greene approach.

Biographers and scholars have documented a remarkable connection between Charles Greene and John Hall. It was said that Charles would visit the Hall shop in Pasadena on his daily rounds, and would engage John on the details of whatever piece of furniture was on the bench. One can only speculate on the nature of these conversations.

APPEALING TO THE SENSES

For Charles and Henry Greene, every detail—however subtle—was designed to appeal to the senses. Nuance flourished in the name of beauty. Elements of utility were reimagined, and made to conform to the Greene standards as well.

Thorsen House, Berkeley, CA, 1908–10. Courtesy California Sigma Phi Society.

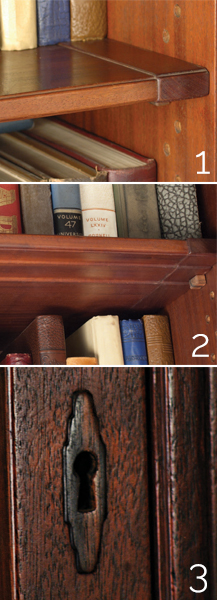

The built-in bookcases (Photo 1) of the 1909 Thorsen House in Berkeley, California, are a prime example. Most woodworkers understand that bookshelves must be beefy to support the considerable weight of books. Most woodworkers understand the dilemma in designing heavy-duty bookshelves that will sustain the weight of their contents without appearing too bulky or unattractive in their design. The Greenes turned this would-be problem into an aesthetic asset.

Viewing the shelf straight on, we see a slender, pleasing profile. Looking on the underside (Photo 2), we see a waterfall detail that not only is aesthetically pleasing but also allows the deeper body of the shelf to gradually become more robust. This detour—in the service of beauty and function—created considerably more work. But apparently, that was of little concern to the designers, makers, and clients.

Another characteristic of Greene & Greene design is that two elements rarely meet in the same plane. Consider, for example, the shelf’s breadboard end. It is proud of the panel in every change of elevation, most of which is on the seldom-seen bottom side.

The use of escutcheons is another prime example of beauty at a cost, as shown in Photo 3. Rather than relying on off-the-shelf hardware (something the Greenes seldom did), they delicately carved and inlaid ebony in place of a manufactured metal piece. Again, this treatment represents an enormous amount of additional work in the pursuit of beauty.

DESIGNS RARELY REPEATED

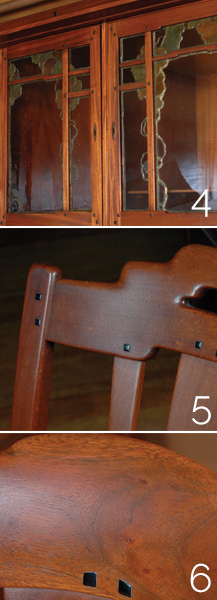

Unlike many of their contemporaries in the American Arts and Crafts Movement, the Greenes did not repeat their designs for mass production. Each piece was designed for a specific client and setting. Details often were developed for these settings and never duplicated. At the same time, a distinctive continuity of style permeates the designs of the Greenes’ mature period (1907–12). Individual settings or rooms, however, were always distinct from one another, as shown in the rocker images. This meant dipping into the well of creativity for fresh material for each setting for every client.

The Greenes’ most productive and creative span—particularly regarding furniture—lasted about seven years, from 1906 through 1912. It was an intense time for the Greenes who received roughly 150 commissions for residential dwellings and their furnishings. The Greenes produced hundreds of individual furniture designs which undoubtedly put an immense strain on Charles Greene’s creative resources. In fact, he took a seven-month period of rest in England in 1909, leaving Henry to keep projects on track in the office.

The detail in Greene & Greene furniture and architectural designs can seem overwhelming. Even among details that were repeated, each instance of their use was reimagined with context in mind. An expedient cut-and-paste was not part of the Greenes’ way of working. For example, they incorporated a inspired cloud lift (frequently seen in Ming Dynasty furniture where it is identified as a humpback stretcher when so used in chairs) in nearly infinite variety, depending upon the setting. Sometimes the pattern would be upside-down, sometimes on-end, and other variations (Photos 4 and 5).

Even the sleek ebony peg was not immune from creative variation, as shown in Photo 6. Observe how the top surface of an ebony peg in the Gamble House master-bedroom chair follows the upward arch in the crest rail.

BEAUTY AND USEFULNESS

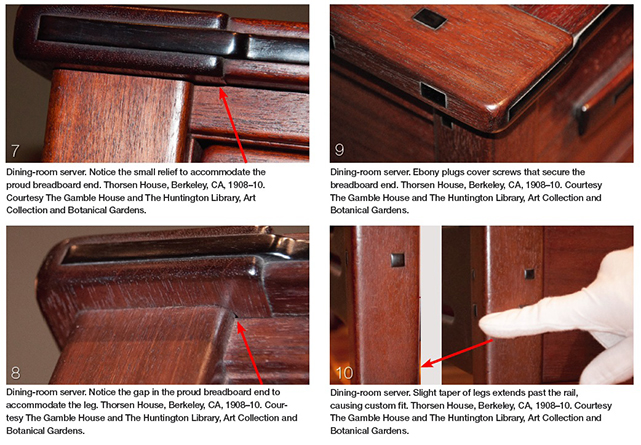

Many of the Greenes’ designs were inherently complex, and seemingly streamlined appearances could be deceiving. The complexity was not present for its own sake, however, but rather was a by-product of beauty and usefulness. At first glance, the 1909 Thorsen server (next page), appears relatively uncomplicated. Under scrutiny its subtlety is revealed. The images of the breadboard end (Photos 7 and 8) shows an end piece less than 1⁄16″ proud of both top and bottom faces of the main surface of the server. The joint between the breadboard end and the panel sits atop the lower structure. The structural member is shaped to accommodate the proud breadboard end.

Rather than forgo the proud detail, the structural member joining the top of the leg is relieved to accommodate the thicker breadboard end. The breadboard end itself is housed, in turn, to accept the leg, as seen in Photo 9. A note of interest: On this server, decorative ebony plugs cover screws that run in slots, securing the breadboard to the solid wood.

The server legs have a slight taper to them at the bottom, extending past the bottom rail, as shown in Photo 10. Because of wood movement, the rail is too wide to be housed. So each rail is custom-fitted to match the shape of the leg. The effect of the extended taper is slight, but one that the Greenes were not willing to overlook.

OBSESSIVE DETAIL COLLIDES WITH PRICE AND DELAYS

Greene & Greene furniture marks an inspiring moment in the history of American design and craftsmanship. In the end, the brothers’ business declined due to the very thing that made them exceptional. By 1913, the Greenes’ uncompromising design and manufacture approach led to escalating prices and recurrent schedule delays.

As a result, the Greenes’ clientele became increasingly intolerant towards them which further prevented their ability to attract new opportunities. For today’s would-be designers and makers, though, the obsessive detail and endless variety of the Greenes’ furniture make the subject a treasure worth years of study.

The best way to experience the genius of Greene & Greene is in their original settings, where visitors can embrace the furniture and architecture as a whole. The Gamble House in Pasadena, California, is the only fully intact Greene & Greene masterpiece. It is open for public tours weekly. Once a month, Gamble House (gamblehouse.org) offers a three-hour Details and Joinery Tour, led by renowned furniture maker James Ipekjian. It’s a must for woodworkers.◆

Interfoto

Resources:

Bosley, Edward R. Greene & Greene (London, UK: Phaidon Press, 2000). Makinson, Randell L. Greene & Greene: Furniture and Related Designs (Salt Lake City, UT: Gibbs Smith, 1979).

Larson, Gustaf. Sloyd (Boston, MA: Sloyd Training School, 1902).

Mathias, David. Greene & Greene Furniture: Poems of Light and Wood (Blue Ash, OH: Better Way Home, 2010).

Peart, Darrell. Greene & Greene: Design Elements for the Workshop (Fresno, CA: Linden Publishing, 2006).

End Notes:

1. Makinson, Randell L. Greene & Greene: Architecture as a Fine Art. (Layton, UT: Peregrine Smith, 1977).

2. “California’s Contribution to a National Architecture: Its Significance and Beauty as Shown in the Work of Greene & Greene.” The Craftsman, August 1912, Vol 22, p 536.

3. Ashbee Papers, January 1909, Modern Archives, Kings College (Cambridge, UK). For more details, see the Summer 2014 SAPFM newsletter.

Leave a Reply