by Anne Mallek

In the last, issue, I wrote about A. C. Vroman’s interest in Japan and his significant collection of Japanese netsuke, which as a young teenager Clarence Gamble had the opportunity to view first-hand. From Japanese tea gardens to curiosity shops, Pasadena in the early 1900s exhibited all of the signs of having succumbed to the international craze for Japanese culture and fine and decorative arts. The Gambles may have traveled to Japan, but many who could not afford such advantages could instead take tea in George Turner Marsh’s commercial tea garden in Pasadena (sold to Henry Huntington in 1911), 01″ peruse the selection of imported art, from China and Japan displayed in the Bentz store on Raymond Avenue.

The artist Toshio Aoki (1854-1912), or “T. Aoki,” came to America in the early 1880s, touring with a group of artisans and performers under the auspices of Deakin Brothers and Company, Yokohama-based exporters of Japanese goods. The story of his life as presented in the press, and presumably by himself, was that he had been a samurai from Aizu, loyal to the shogunate and jailed following the Meiji Restoration. Following his stint with the Deakins tour, he worked for George Turner Marsh in San Francisco, another importer of East Asian art and curios. He was also hired as an occasional illustrator for publications like the San Francisco Call and The Californian illustrated Magazine. A 1908 article in the Japanese journal Kaiga soshi (Painting Digest), described him as “the person who is known among the greatest number of Europeans and Americans, to the extent that it would be an embarrassment to fine ladies and gentleman had they not heard of him.”1 The article goes on to assess his work as more that of a performer than an artist: “[Aoki] does not necessarily excel at the techniques of Japanese painting; instead, he enchants the Amerlcans with his strange talent and distinctive social skills.” An article in the Los Angeles Times in December 1914 further identified this “celebrated artist and philanthropist, known to America and throughout Europe…prominent in Pasadena” as a set designer for local theatrical productions, including: “Madame Butterfly” and ‘The Darling of the Gods.”

Aoki appears to have been coming to Pasadena from the 1890s, working for Marsh, and eventually establishing his own studio in the Hotel Green. The fourteen-year-old Clarence Gamble paid him a visit there in February 1908, even taking a picture of the artist at work. It was not long before Aoki had established a reputation for hosting elaborate Oriental-themed parties at the hotel and elsewhere.

In addition to his set designs for theatrical productions, he was known for painting the rooms (as well as their: parasols, scarves, and even gowns!) of wealthy clients living on Orange Grove and Grand Avenues.2 The Times article of 1914 noted that “[h]e is remembered particularly for his lavish expenditure for things social. He once gave a dinner at the Hotel Green in honor of J. Pierpont Morgan which cost something like $2000 for the night’s entertainment.”

Greater than Aoki’s own renown, however’, may have been the fame of his adopted daughter, Tsuru Aoki (1892-1961), who would become the first Japanese-American silent film actress. Tsuru, in her own account of her childhood (as reported in the Times article of 1914), recalled coming to America at the age of 6 with her aunt and uncle, both members of a Japanese kabuki theater company. Finding themselves destitute in San Francisco, Tsuru said, “One day a very little man, a Japanese, with the kindest face I had ever seen, came to call. My aunt cried a great deal and told Aoki, for it was he, that it, was because of her failure in America. She had been so successful in Paris and London, where she had previously played.” Tsuru was left to live with this new uncle, whom she came to think of as a father. Her aunt, Sada Yacco, was later dubbed “Japan’s most famous actress,” claiming to have performed for the Prince of Wales (the future King Edward VIII) in London.

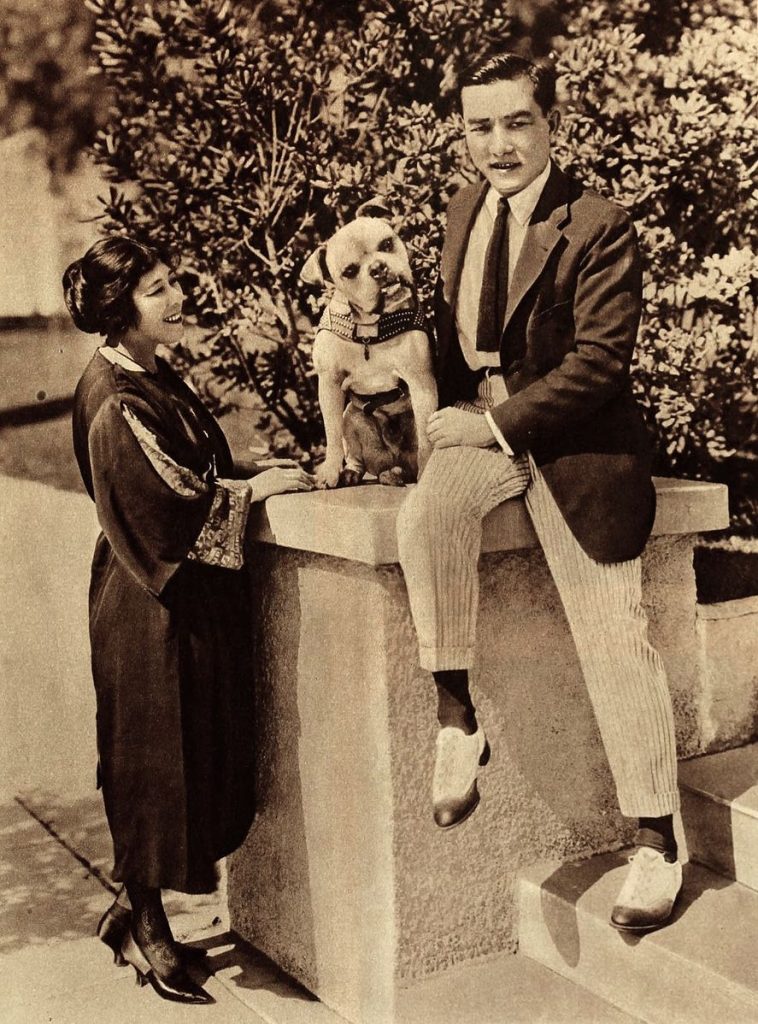

Aoki would never see his daughter on film, dying a year before Tsuru’s fllm debut in The Oath of Tstura Sorz (1913). She married fellow fiIm actor Sessue Hayakawa (1889-1973) in 1914, starring in over 20 films with him.

She was variously cast in roles that, reiterated Oriental stereotypes or enlisted her background to represent outmoded Victorian ideas and societal constraints.3 While in America she was proclaimed to be “one of the most highly cultured Japanese women in this country.” Even the Japanese theater world sought her assistance as translator (both linguistically and culturally) of the plays of Shakespeare and Sheridan for performance in Japan. Aoki ultimately performed in nearly 40 silent films between 1913 and 1924, when she retired from the industry to raise her family.

Hayakawa was the first Asian-American leading man in Hollywood in the early 1900s, acting for directors such as Cecil B. DeMilIe and attaining a salary of $5000 a week. In 1918, he founded his own production company, Haworth Pictures Corporation, which helped to make him one of the highest paid silent-film stars of the 1920s. Hayakawa would go on to produce, star in, and distribute as many as 23 films through HPC, which was involved in every aspect of the films’ production from marketing to casting and editing. He may be best known to us today for his Oscar-nominated role as Colonel Saito in “the Bridge on The River Kwai” (1957).

I realize that the Gambles have not featured prominently in this article, but I’ll leave you with a few final thoughts. Given what we know of the Gambles’ interaction with Aoki, and the careers of his adopted daughter and her husband, one could say that there are only two degrees of separation between the Gambles and the stars of silent film (and just three degrees of separation between the Gambles and Alec Guinness!). For additional reading, please take a look at the materials footnoted in this article.

Footnotes:

1 See the article by Chelsea Foxwell, “Crossings and Dislocations: Toshio Aoki (1854-1912), A Japanese Artist in California,” in Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide, Volume 11, Autumn 2012. www.19thc-artworldwide.org/autumn12/foxwell-toshio-aoki-a-japanese-artist-in-california.

2 It was Orange Grove Avenue until 1912, when it was re-named Orange Grove Boulevard.

3 See Sara Ross, “The Americanization of Tsuru Aoki: Orientalism, Melodrama, Star Image, and the New Woman,” Camera Obscura 20.60 (2005): 129-158.

Leave a Reply