by Anne Mallek

We are all aware of the influence of Japanese design in the Greenes’ work, and of the popularity of Japanese culture in and around Pasadena when The Gamble House was being built – whether embodied in George Turner Marsh’s Japanese tea garden, or the half-dozen or more purveyors of “Japanese Art Goods” listed in the city’s directories. The Pasadena Daily News thus declared with some authority in February 1907, “The rage for Japanese art that prevails in all society and art educational circles in the east, has at last struck Los Angeles.” This is the first of two articles in which I’ll be investigating some lesser-known Japanese connections with the Gambles and some of the people that they came to know in Pasadena.

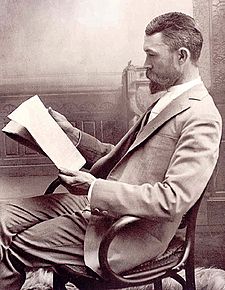

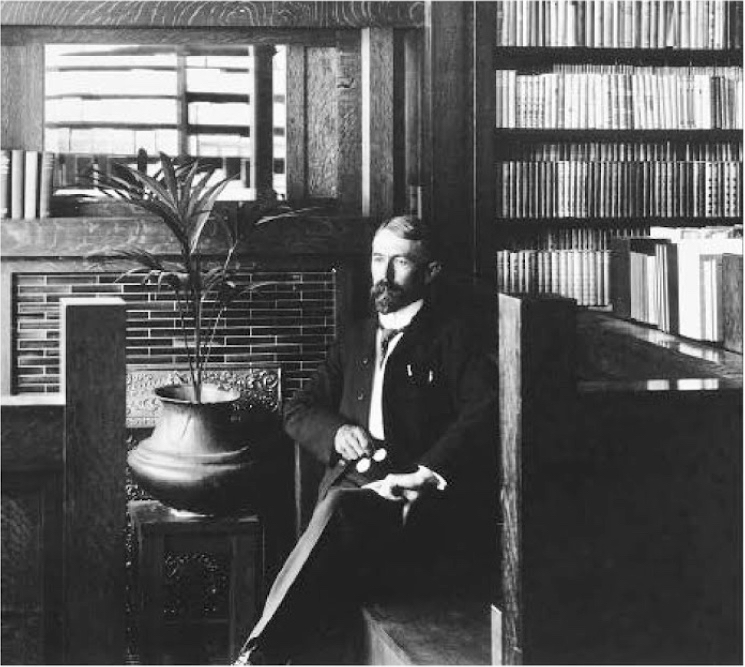

We know Adam Clark Vroman today for the bookstore he established on what was then Colorado Street in 1895. Avid photographer as well as bibliophile, he also sold photo supplies at the store, and was one of the first Kodak agents in Southern California. From his letters and journals in 1908 and 1909, we know Clarence Gamble was a frequent visitor to the store to feed his own burgeoning interest in photography. The film and developing supplies were then put to good use in the new basement darkroom at 4 Westmoreland Place.

Vroman is and was also well-known for his keen interest in southwestern and Native American culture, documented in the hundreds of photographs he took of Pueblo villages, missions, and native peoples between 1895-1904. His fascination with Japan may perhaps be less familiar, to many of you, and was something he pursued in later years, at about the same time that the Gambles and Greenes were becoming interested in it as well. During the Gambles’ trip to Japan in 1908, Clarence even mentioned in a letter that in Yokohama “we went to the photographer that Mr. Vroman had recommended to us and found that he was fine. Some of the transparencies he had were beautiful—one of Fuji especially. The lantern slides were fine and very well colored.” Vroman had been visiting Japan since 1903, and was even in the country in 1908, though it remains uncertain whether he met with the Gambles there.

A journal entry of March 4, 1908, records a particularly busy day for then 14-year-old Clarence, and included visiting Mr. Vroman: “Went to lot AM. Got chased home by rain. Studied a lot. Went to Blacker house Oak Knoll PM. Got new camera. Went to Mr. Vroman’s after dinner. Saw a fine collection of Netsukes from Japan.” By this time, Vroman had become rather famous for his collection of Japanese netsuke, not least due to his recent sale of 2500 netsuke to wealthy philanthropist Mrs. Russell Sage, who in turn gave them to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. In its April 1911 issue, the museum’s newsletter boasted that “As a collection it is thought to rank with the largest collections in Europe including the famous collection in the British Museum.”

You might well ask, what is a netsuke? Its evolution is very much an Arts & Crafts story, in which items of daily use were carefully crafted and made beautiful. Netsuke first made their first appearance in the 16th and 17th centuries in Japan, during the tenure of the Tokugawa shogunate. It was then becoming fashionable to wear inro, or small cases for holding objects that were suspended by a cord attached to the obi, or sash. The netsuke was created as a kind of toggle for the cord to secure the inro to the obi. Netsuke were most often made of stone, shell, bone, or wood, depicting subjects drawn from Japanese and Chinese mythology, religions, and folklore. As they became more popular they also became more varied in form and more detailed in their carved decoration. When Japan opened to the west in the mid-nineteenth century following 200 years of isolation, these small, highly-decorated objects became much sought-after by western collectors, Vroman not least among them.

The Pasadena Star News ran a feature on Vroman’s collection on September 17, 1914, headlined “Netsukes Hold Wonderful Charm: Quaint Little Japanese Carvings Embody Much of Beauty.” Its author, Gussie Packard Dubois, described the experience of being invited into Vroman’s home to “gloat over the rare and beautiful Japanese handicraft which for years he has been gathering in his trips abroad.” As Vroman brought out tray after tray of the exquisitely carved objects, Dubois noted “the fineness of the polish on each netsuke,” so that you desire to hold them in your hand and feel the unbelievable finish.” Unwittingly, perhaps, she was attracted to the objects by their aji, a Japanese term that described the way the artist, could communicate his spirit through touch as well as sight. It is a spirit that I think we also feel in looking at (and very occasionally touching) many Greene & Greene-designed objects, and that the Gambles would no doubt have shared.

If you are interested in reading a particularly interesting story about a collection of netsuke, I recommend The Hare with Amber Eyes by Edmund de Waal. To view some examples of netsuke in person, you might visit the Pacific Asia Museum locally, or LACMA, both of which have fine examples of netsuke and inro in their collections.

Originally published in the Greene Sheet December 2017

Leave a Reply